Status Anxiety – and how walking changed my life

“What do you get out of it?”. I suppose all those who spend days and nights immersed in the outdoors have been asked that question. Most people cannot understand the appeal of nights alone in the hills. Whatever answer you might give, the chances are that they will remain unenlightened. For some of us it’s to find that small part of ourselves that is easily smothered in the hurly burly of what passes for life. Call it what you will – your soul if you must – but without it we are surely diminished.

It was in the early noughties, when things were really on the up and up and buying a new car or whatever was a matter of writing a cheque (remember them?) that I realised that life had somehow become pretty miserable. I was putting in overlong hours and dealing with difficult people for much of the time. Still I carried on. Money and ambition are curious things and cause us to behave in curious ways – good and bad. Yes, they can drive us on to achieve great things and improve our lives. But the compulsion to succeed can also drive us slightly mad.

I went slightly mad.

The only periods of sanity were when I went up to Scotland on the sleeper with my old mate, Alan Sloman, to go backpacking for a few glorious, liberating days. Taking part in the TGO Challenge was just fantastic – two weeks of freedom from email, laptop and phone (I told the office that none of these worked in the Highlands. I didn’t tell them that they didn’t work because all the devices were switched off and in a drawer at home).

I loved backpacking, especially the enforced egalitarianism of having nothing but what you can carry. No matter how much money you might have, you can only carry so much stuff. In fact, carrying too much is likely to provoke ridicule – quite the reverse of ‘normal life’ where the main point of toil, beyond survival, is the accumulation and display of as much stuff as possible.

Gradually, gradually, walking changed my life. In 2005 I sold my company to my co-directors. The truth is that I had just stepped off the treadmill for a while, but then a cancer diagnosis in 2008 and the subsequent surgery, with months of follow up treatment, changed my perspective completely. Whilst I was unwell, my old company was struggling with the fallout from the 2008 financial crisis. A few months later it failed, taking my remaining stake (and most of my retirement fund) with it.

Disaster? No. Not really. I soon discovered that living simply isn’t terribly expensive and is vastly more pleasurable.

Now, at this point it might appear that I’m about to say that I became some sort of hermit, living in a shack and eating berries and roots gathered from the woods. Not so. I still like to excel when I take on a task and, as anyone who knows me is well aware, I love my luxuries and take great pleasure from them. The difference lies in being able to distinguish between personal luxuries and status symbols.

The breakthrough for me was the realisation that the pleasure that I had once gained from acquiring some expensive gewgaw tended not to add greatly to my stock of satisfaction and happiness – at least not after the first rush of delight. So I just stopped pursuing them. Miss W is of a similar mind. In fact she got there long before me. And many people that I meet whenever I amble across Scotland on the TGOC are seemingly made this way.

Comfortable in their own skin.

Beyond the basics (food, shelter, security, sex) many people are driven not by personal goals but by the craving for high social status, whether merited or not. If one can’t acquire genuine status and respect, then the next best thing is to acquire the badges of status. This, no doubt, is why so many run up huge debts just to parade around in designer labels, drive expensive cars and mortgage their grannies to buy unaffordable houses filled with designer kitchens, ever bigger televisions and the like. Lives dominated by the fleeting triumph of having the latest must have, and the misery of envy whenever a friend or colleague trumps them.

“It may be tempting to laugh at those afflicted by urgent cravings for the symbols of status: the name droppers, the gold tap owners. … Rather than a tale of greed, the history of luxury could be more accurately read as a record of emotional trauma. It is the legacy of those who have felt pressured by the disdain of others to add an extraordinary amount to their bare selves in order to signal that they too may lay a claim to love”

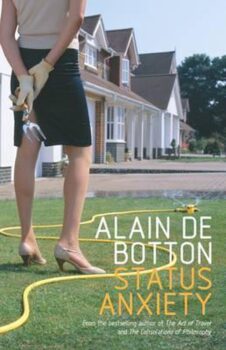

Alain de Botton.

We all worry about what others think of us. We all long to succeed and fear failure. We all suffer to a greater or lesser degree – usually privately and with embarrassment – from status anxiety. Alain de Botton analysed the angst that this condition provokes in his 2004 book “Status Anxiety”. For a book by a philosopher it is remarkably readable, and neatly points up the diminishing returns of increasing wealth. It’s not one of those books that will ‘change your life’, but it may make you think about it …

… and maybe understand why the people you see inside the most expensive cars always seem to look so damn miserable!